Apnews:

Governance is ultimately about intent, integrity, and outcomes. Achieving stated objectives and fulfilling public promises require administrative commitment and political will not cosmetic alterations. What, after all, is achieved by merely changing names? How does it benefit citizens? Of late, a peculiar obsession appears to have gripped those in power: the belief that renaming schemes amounts to reform.

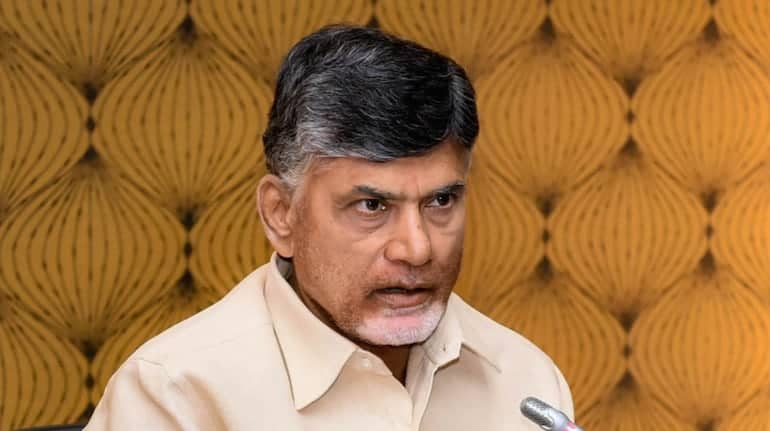

At the national level, the BJP-led NDA government has proposed not only renaming the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme but also altering its structure. In Andhra Pradesh, the current coalition government is preparing to rename the village and ward secretariat system introduced by the previous YSRCP government. Instead of correcting systemic failures and operational shortcomings, the State Cabinet has chosen the route of legislation bringing in an ordinance to rechristen the institutions as “Swarna Grama” and “Swarna Ward”.

This fixation with “gold” is not new to Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu. Over two decades ago, he spoke evocatively of “Swarna Andhra”. Today, when gold and silver prices are soaring far beyond the reach of ordinary citizens, the question arises: what relevance do such gilded labels have for public institutions meant to deliver services efficiently and equitably?

A System Designed for Decentralisation

The village and ward secretariat system was introduced in Andhra Pradesh in 2019 with the objective of decentralising governance and bringing government services closer to citizens. The model envisaged delivering welfare benefits such as pensions, along with services related to revenue, education, healthcare, electricity, agriculture, animal husbandry, and women’s safety, directly at the grassroots level.

Each village and ward secretariat was staffed with around ten employees, recruited initially on consolidated pay and later absorbed into regular pay scales. Complementing this structure was the volunteer system one volunteer for every 50 households tasked with bridging the gap between the State and citizens. Volunteers assisted in pension delivery, certificate facilitation, application processing, and grievance redressal, receiving a monthly honorarium of ₹5,000.

At its peak, the system comprised over 15,000 secretariats, employing approximately 1.34 lakh staff and 2.52 lakh volunteers, delivering around 500 services across 35 departments. The goal was time-bound service delivery, with most grievances resolved within 72 hours.

With the change in government, the volunteer system was dismantled. Their responsibilities have only partially been absorbed by secretariat staff. Today, roughly one lakh employees remain, and the system shows clear signs of administrative fatigue.

When Objectives Fade, What Value Do Names Add?

As one Andhra Pradesh Minister reportedly remarked in a private conversation, “When people cannot afford even a gold earring due to soaring prices, what meaning do ‘Swarna Grama’ and ‘Swarna Ward’ really have?” The observation captures the dissonance between political symbolism and lived reality.

This is not the first time grand visions have been sold to the public. Mr. Naidu’s Vision 2020 document was once dismissed by then Opposition leader Y.S. Rajasekhara Reddy as a “decade-long fictional exercise.” More recently, the Union government and the Telangana government have begun speaking of Vision 2047, projecting ambitions two decades into the future without adequately addressing present governance deficits.

Telangana, too, witnessed similar symbolism under K. Chandrasekhar Rao’s slogan of “Bangaru Telangana”, a phrase that became the subject of internal satire within his own party. Even the Congress party’s 2023 election promise of providing one tola of gold and ₹1 lakh cash to poor women at marriage failed to translate into reality.

In governance, such rhetoric often remains illusory. Gold, repeatedly invoked, rarely materialises beyond slogans.

A System in Distress

On the ground, many village and ward secretariats lack even basic facilities. In several offices, there are no funds allocated for sanitation; employees reportedly pay from their own pockets to keep premises functional. A Deputy MPDO acting as nodal officer candidly admitted that there is “zero budget” even for essential maintenance.

Secretariat employees many of them well-qualified and recruited with aspirations of meaningful public service express resentment over the erosion of role clarity and lack of recognition. Tasks once performed by volunteers are now being offloaded onto them without corresponding administrative support. Unsurprisingly, absenteeism and disengagement are becoming increasingly common.

A statewide study by People’s Pulse Research Institute on the functioning of the secretariat system reveals worrying trends. Without immediate corrective measures robust monitoring, administrative control, coordination, and accountability the system risks imminent collapse, despite substantial public expenditure.

Ironically, even as this study was underway, the Cabinet announced its decision to rename the system.

Reform Demands More Than Rebranding

There has been criticism that the secretariats were overstaffed. In response, the government has initiated a rationalisation process, reducing staff strength from 11 to 6–8 employees per secretariat, based on population. However, this exercise has been poorly implemented, causing confusion and inefficiencies.

What is required is not symbolic renaming but structural reform ensuring optimal staffing, restoring service delivery timelines, and reinforcing administrative accountability. If strengthened, this decentralised framework could still serve as a pathway towards Gandhi’s vision of Gram Swaraj.

Governance Is a Continuum

Governments may change, but governance itself is a continuous responsibility anchored in accountability. Those who discard earlier policies and nomenclature without due evaluation must reflect on their own moral authority to announce long-term “visions”. If every incoming administration dismantles what came before it, governance becomes cyclical disruption rather than sustained progress.

Correcting flaws, refining implementation, and improving outcomes are the true markers of reform. Renaming schemes without addressing systemic decay merely amounts to cosmetic governanceg old-plating structures hollowed out from within.

Public administration must focus on delivering services effectively and respectfully to citizens. That alone is the essence of democratic duty.

R. Dilip Reddy

Political and Social Analyst; Director, People’s Pulse Research